[Author’s note: I’ve known the Ives family since Daniel Ives’ younger sister Jill was a babysitter for my children years ago. I have such fondness for Martine, Jill, Emily and, of course, Danny, and I was thrilled to see Danny open his Maplewood Bike Shed just six months ago. At the time, I wrote an article on the opening and shot a video for The Village Green, which was quoted in the new story they ran after his passing. So, as a personal and family historian, it seemed fitting that I should endeavor to pen a profile of his extraordinary life, cut far too short. I hope this gesture brings some solace, and a smile, to the family, and myriad friends who loved him deeply.]

Danny Ives

To hear his mother Martine Ives tell it, Danny Ives was a force from babyhood who never sat still and was not interested in relaxing. “He was always wanting to stay up and not sleep,” she laughed, “and he stayed like that. Like he’s gonna miss something.” A restless, energetic kid who was adored by all his teachers and peers, but didn’t always enjoy the rote parts of school (he’d rather have been building bikes from parts, drawing complex mechanical diagrams or out riding), Danny thrived on freedom and exercise. “They used to call kids ‘hyper’, and he had that kind of energy,” Martine said. “I let him do the bike stuff a lot when he was younger, because it would make him so tired. I’d say, ‘Hey, go bike riding,’ and he would be out for hours, come home, eat and go to sleep!”

Danny’s younger sister Emily said not much changed for Ives as an adult. “He didn’t lay down for a second,” she explained. “If he went to bed late, he was still up early. You would never catch him watching a movie, because he was always up doing something, going somewhere. And when he would lay down as a kid, you’d know there was a problem.”

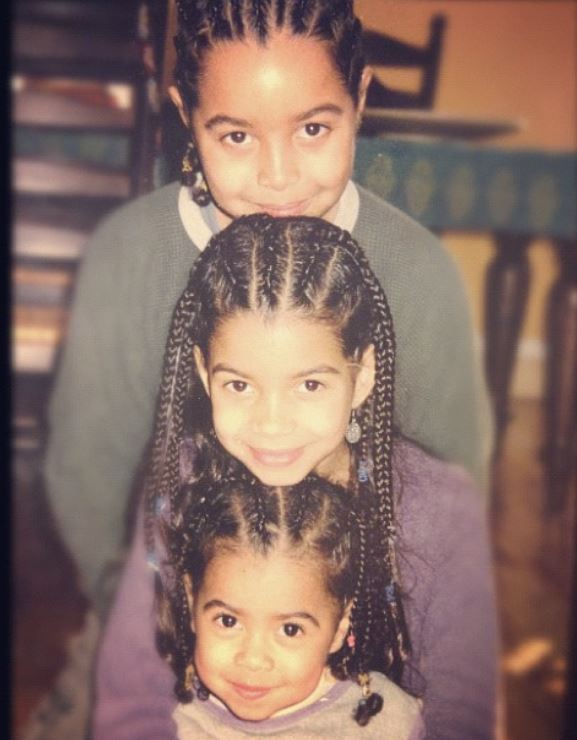

Danny (top) with sisters Emily and Jill

When the school would call Ms. Ives and say that Danny couldn’t sit still, she wasn’t angry. “He always had to move around a lot. They wanted me to speak to him about raising his hand, which he would do quickly, even if he didn’t know the answer. But I knew that Danny focused on what he was interested in.”

Everyone could see it, especially Emily, who looked up to her big brother. “Danny was a genius; he loved bikes, so his focus was on bikes, and that thing that he loved that was not taught in school,” she said. “As a kid like that, school could limit you, make you feel bad about yourself, but he never stopped believing in himself.” Then she paused. “You can’t sit a kid down whose talents are to be a people person.”

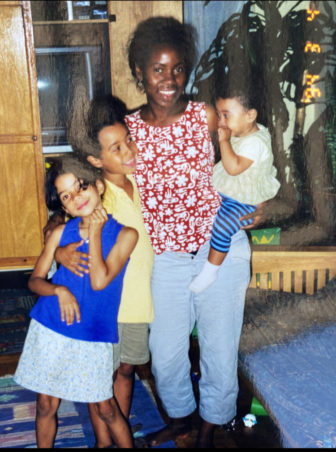

Martine Ives with Jill (right), Danny and Emily

Gifted socially and at ease with anyone, Ives’ warm smile made everyone “feel like family,” shared childhood friend and long-time girlfriend Brianna Medina. “He would always give a friend a place to sleep, even if they stayed too long,” she laughed.

In the days following his tragic death last Friday night, when he was killed in a motorcycle crash, Medina has heard from dozens of friends of hers and Danny’s who shared stories and ways in which Danny made them feel welcome, comfortable or included. Shy people or quiet people never had to sit out gatherings; Danny made sure they fit in and weren’t awkward.

And, he always liked to make people laugh, going so far as to take on female roles in Shakespeare plays. In Stacey Lawrence’s Columbia High School drama class, Danny agreed to play the part of Thisbe, the female lead in the Mechanics play within a Midsummer Nights Dream for the Shakespeare Festival, which was performed for the entire school.

“Danny brought the house down in laughter,” Lawrence recalled. “In the last scene, he was being chased by a fellow student dressed as a lion, and Danny had his chest stuffed so that it bounced as he ran. I think he had a wig on, too, and I remember him doing a lot of curling of the wig with his fingers. He always made class fun and bright.” Lawrence said she’s taught thousands of kids, but remembers these moments with Danny most vividly.

As a bicycle and motorcycle-obsessed kid, Ives began to rummage through people’s curbside junk on days when the South Orange Department of Public Works told residents to put out their unwanted items. For him, the old bikes he found were not trash, but treasure. “Anything I could get my hands on, I would kind of tinker with it, take it apart, put it back together,” he said. “Then I started fixing other people’s bikes from my mobile van.”

“Danny was legendary to me,” said Medina. “He would take apart an entire motorcycle, and put it back together again in under a week,” she remembered. “I wouldn’t think he could remember where everything went, but then, he always could.“

It was a philosophy of building something from nothing that he shared with one of his industry idols, custom motorcycle builder Maxwell Hazan of Hazan Motorworks, whom he visited in 2017 on a trip to Los Angeles. “Never did I ever expect to meet a legend,” Danny wrote on his Instagram. “Turns nothing into something, continuously testing his abilities and learns something new with every build. It’s all about paying attention to the details, because it’s the little things that hold everything together.” In a way, perhaps without realizing it, Danny himself was the not so “little thing” that was the glue for so many in Maplewood and father afield.

“Before I moved to Colorado a few years ago,” recalled best friend Nick DiChiaro, “I talked to Danny. I asked him what he thought, and he told me to keep my head high and follow my dreams. Ever since we started riding bikes as kids, we talked about starting a bike shop.” That dream, years later, was realized with the foundations of the Maplewood Bike Shed.

Danny and Nick DiChiaro at work on one of Danny’s bikes

“About a year ago, Danny brought me to what would become the Bike Shed, and he said, “I think I found my place.” It had no floors, no bathroom, but he made it so beautiful.” Since the spring, DiChiaro said, Danny asked DiChiaro to send bikes for him to sell from Colorado. “He knew it was my dream as well, so in his way, he made sure to include me.”

Hazan, reached by phone in Los Angeles, said he instantly recognized in Danny the trait of seeing possibility in what doesn’t yet exist, and creating something with imagination. “He walked in, and was clearly a really smart guy,” Hazan remembered. “Danny had the exact quality I look for when I have someone working for me – someone smart, but more than that, willing to think creatively.”

They had tacos at a little stand downstairs on East Pico Boulevard, and as they spoke, Hazan said he knew he had met someone kindred. “You can kind of smell that quality when you meet someone, if you have it yourself. I would go to junk stores when I started out, too, and get the cheapest things I could find to build with,” he recalled. “Looking at junk parts is something most people can’t do, because a faucet can be turned into something completely different, but not everyone has that vision. Danny didn’t need a manual; some people can build upon what they have seen, but most can’t see things that aren’t there.”

Danny loved building motorcycles, especially those from the 1980s. He was often pictured alongside his beloved Hondas and Ducatis, and shared photos of himself working with parts or on long rides, something he enjoyed. Medina recalled a day when they rode up to the Catskills together, just the two of them, following the winding roads and feeling free in the wind. For her, keeping up with Danny on a motorcycle was an accomplishment.

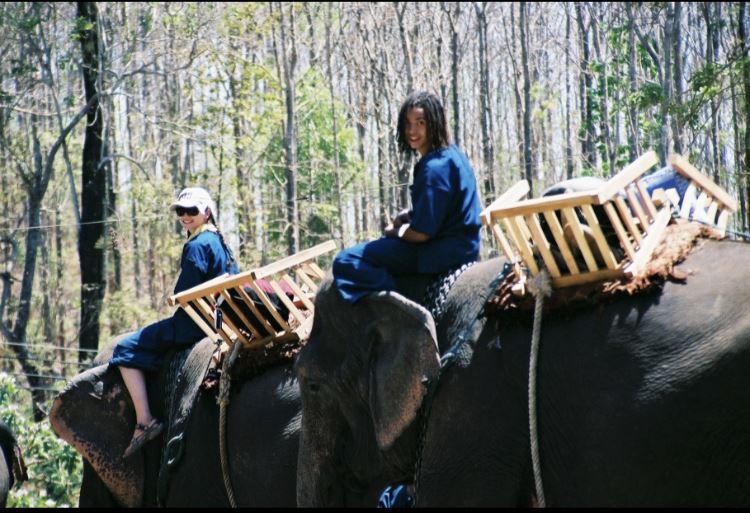

Danny and his elephant Pang Me in Thailand

While at Maplewood Middle School, Danny applied to be one of six teenagers on celebrated news producer Linda Ellerbee’s Nickelodeon show, Nick News Adventures. He was selected from a large pool to go to Thailand with Ms. Ellerbee where along with five other American fourteen-year-olds, he spent two weeks with a television crew living at an elephant sanctuary in Chang Mai. Each student was assigned an elephant to care for during the trip, and Danny’s Pang Me took him through the jungle, played in the mud with Danny, and was fed by him. Of the six, Danny’s father (who was a chaperone), recalls, his son was the only one to feel comfortable enough with host Ellerbee to embrace her openly, and to make a friendship. He was shown with his arm around her, laughing, in a News Record photo at the time. Upon hearing of Ives’ death, the now-retired Ms. Ellerbee had this to say about her time with Danny, and the indelible impression he made:

Nick News was a television series that tried to explain the world to kids: the behavior of nations, the evolution of ideas, the health of the planet and all its inhabitants. We told kids life could be an adventure. We took kids to experience worlds that were unfamiliar to them…I remember Danny’s smile when he met his elephant.

Danny had the sweetest smile.

Did he talk to his elephant? Did he sing to his elephant, play with it, laugh with it, let the elephant spray water all over him in the river? Did he ride on, romp with, and care for his elephant, all day, every day? He did. All the kids did. But when the time came to return to the US, only one kid cried when he said goodbye to his elephant.

Only one.

It was a special moment. Danny was a special young man. He showed us a heart as big as that elephant. He showed his love.

I wish I had known him better. Longer.

We all do.

With sadness,

Linda Ellerbee

When he wasn’t charming strangers, Danny excelled in his constantly expanding world of things on two or four wheels, and the greatest skillset for life possible, perhaps: that ability that can’t be learned or taught, which is to make anyone feel like they were your oldest friend. “He would always stand up for kids who weren’t as popular,” says Ms. Ives. “He would approach the ones who were entitled, and tell them to include the others.”

Childhood friend Jack Zichelli echoed that if Danny overheard someone badmouthing someone else, he’d step in to help the person being bullied, and never allowed anyone to be left out or left behind. “If you met him for the first time, you’d feel like you knew him for five years,” said Zichelli. “Danny was always there to talk to people, and helped everyone. You could call him at 2 am, and he would answer.”

Notorious for fixing mechanical problems or giving driving advice to strangers and friends alike even at sixteen, Zichelli remembered what Danny did when a car on South Orange Avenue broke down, because the driver didn’t know how to work a manual transmission. “He made us pull over, and Danny said, ‘I have to teach this guy to drive!’ – and you know, he did.”

Danny Ives was clearly a man who lived life on his terms, and without fear. He had an innate understanding of how to make something broken whole, whether it was a bike or car part or a person. “We were having a bad day a few years ago, and Danny said, ‘Tomorrow the sun will rise, and we will try again,” recalled DiChiaro. “He wasn’t kidding, or saying it with irony. Ever since he told me that, I live by it.”

When they walked into the first day of 9th grade at Columbia high school wearing the same shirt and outfit – an ACDC t-shirt and skater clothes – DiChiaro said everyone called them “twins”, despite the fact that Danny was a lot taller, and DiChiaro was skinny.

A photo from that day is DiChiaro’s very favorite, with Danny enveloping the smaller teenager in a giant hug, showing the other kids his friend was cool – and burying DiChiaro’s head in his chest with a giant smile on his face. “He made people feel 100% all the time, and he would never put them down.”

Another close friend, Elyssa Claudio, said that despite his love of speed, Danny understood very clearly the value of slowing down, and how his beloved bikes fit into the bigger picture of happiness for so many. This was part of the reason he wanted top open a bike shop. “He felt like bikes helped people slow down, and connected people to their inner child,” she remembered. “Even though Danny loved speed, and he was extreme, it’s true – when you get on a bike, for a bit, you feel like you’re ten again.”

“Danny collected characters,” explained Claudio, “and he made you love them, too, even if you didn’t like them. He would take care of everyone and give everyone a home.” This inclusiveness extended to younger men who worked in the Maplewood Bike Shed, most of whom Danny had known for years. One such young man, now around 21, knew Danny from the age of 9, and told Claudio recently that he feels Danny saved his life by keeping him off the streets. Ives taught him BMX tricks, and understood that school wasn’t for easy for everyone. The same generosity of spirit was on display when Danny and Nick DiChiaro began hosting skate and bike gatherings at Maplecrest skate park years ago, with Danny taking younger riders and skaters under his wing and showing them not only tricks, but the right way to be.

Both the bike tricks and surety about what he wanted started early.

In their tiny one bedroom Brooklyn apartment, where Danny lived until he was 7, his mom and dad remember that he would ride a plastic toddler bike, which he insisted on having the training wheels removed from before age 2. “He wasn’t speaking yet,” remembers his dad George Ives, “but he made sounds and pointed so it was clear he was not having those supports on the bike.” Once unfettered, Danny rode the little baby bike up and down the hallway so often, said Martine, that the lady downstairs poked the ceiling with a broom, and complained about the noise. So, his father started taking him to nearby Prospect Park, where Ives would give Danny one push, and he would just go, without knowing where the brakes were.

By three, “Danny started playing with lots of cars and taking them apart,” remembers Martine. He’d pull pieces off with intention, and just when they thought Danny was breaking the toy and went to scold him, they began to realize he was “just changing it to make something else.”

And taking one thing apart and creating something else, taking a cue from an old piece of machinery or household item, was what Danny did best. “I want to build stuff,” he’d always tell him mother. “I’d say, “How are you going to build stuff?” Ms. Ives laughed softly, “and he said, “Mom, watch.”

“Danny would take this remote-control toy car called the “Tantrum” to first grade at PS 321 in Brooklyn, and race it in the courtyard. He could drive it through crowds from where he was standing, and not hit anyone,” said his father. Whether with tiny or life-size toys, Danny had a gift. “It wasn’t just the acumen for driving,” explained Ives, “but he was really good at making diagrams for science in school. Every once in awhile, he’d pick up a pen write a poem that would make me cry.”

And, Danny made everything fun, so it seemed larger than real life. “We were eighteen months apart,” said sister Emily. When we lived in the one-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn, my parents, Danny and I all shared a bedroom. We had bunk beds, my parent’s bed, and when Jill was born, Jill’s crib was placed on the other end, so you could say it was cramped,” she remembers. “The foyer felt huge to me by comparison, with Danny there, and we would sit in that actually tiny area by the door on our computer playing pixilated Frogger, and make forts out of the desk, inventing games.”

For a man who wasn’t typically afraid of anything or squeamish, Claudio said Ives was terrified of live spiders, but apparently unafraid to eat other insects or unusual foods. This included his appetite for extreme sandwich condiments. “Danny was disgusting,” she laughed. “Every sandwich had to have pickles and pepperoncini on it. He’d get a bacon egg and cheese with jelly and ketchup and more.” While in Thailand with Ellerbee, Ives was happy to eat spinach for breakfast or “other crazy things,” he told the News-Record, like ant eggs, deep fried worms and baby bees. Danny tried them all. “The ant larvae were still alive, and I was the first one to try them,” he said. “I just took a handful of ant eggs. It tastes kind of like a protein shake.”

After graduating from Columbia High School, Danny worked both construction and hospitality jobs with friends, bolstering his knowledge of how the things he loved to build worked, with robotics studies at Morris Community College. Zichelli, who Danny met in middle school when he had a crush on Danny’s younger sister Emily, remembered those days fondly. “I went by their house with Emily, and Danny kind of looked me up and down, like he didn’t have a good feeling about me,” Zichelli laughs.

“He looked like he was thinking, “Who’s this guy?” But, when Danny walked outside the house and saw my BMX bike, he thought, “This guy’s not too bad after all!” We hit it off right there.” For her part, Emily remembers it the same way, but with a twist. “I couldn’t have a boyfriend because Danny was friends with all the guys,” she said. “I dated Jack for a bit, and once he saw Danny’s bike, he broke up with me to be Danny’s friend,” she laughs. “He stole my boyfriend. But, Jack ended up becoming like family, which was how everyone ended up with Danny.”

Jack and Danny landed their first jobs together, Jack remembered, mostly to get back in Martine Ives’ good graces. “We were both sixteen, and got in trouble with his mom, so we thought, “We’ve got to get a job!” Hired on at Above restaurant, then over Ashley Marketplace in South Orange, the boys “put the whole place together.” Later, the summer after high school, Jack and Danny build a custom shed for a customer, creating a small odd-job business together which they called “Jack Daniels”. Later, Danny worked for the South Orange DPW, where according to sister Emily, his nickname was “Happy”, because he was.

Photos from Ives’ Instagram account depict a lifelong love of BMX bikes and motorcycles, including photos and videos of Ives doing jaw-dropping aerial tricks and stunts on skate ramps and buildings. A skilled athlete, Ives competed in swimming and gymnastics starting in middle school, and could often be found at the Maplewood pool doing complex flips and dives, much to the delight of watching children – who cheered and clapped their hands. Ives would emerge from the bottom of the pool with a huge grin on his face, happy in their joy.

“Danny would do gymnastics whenever he felt like it,” Medina laughed. “It could be anywhere, and there would be Danny, doing flips.” On the beach, or running up a tree trunk with only a 10-foot start like Donald O’Connor’s brick wall trick in Singin’ in the Rain, always landing, cat-like, on his feet after a flip. “He was good at everything he tried,” said Medina. Then she laughed a little. “It was frustrating that everything athletic was easy for him!”

Once, his father planned to take Danny skiing in New Jersey when he was 11 or 12. The week before, every day, Danny sat with his face in a computer monitor, looking at videos of snowboarding. “He just spent hours absorbing it all, and I swear, at the mountain he chose a snowboard over skis, got on it, and snowboarded as though he’d been doing it all winter.” So adroit with anything he wanted to do, whether it was dancing or singing or riding a motorcycle, Danny could do figure it out. “That’s kind of how I saw him,” said Ives. “He chose what he wanted in life to do, when he wanted it, and he did it. The same is true for the big picture. He had his mind on living what he loves, helping people with their bikes, and BMX. Everything he touched turned into a work of art.”

Building just about anything came easy for Danny, too, and when they spoke, specialty motorcycle builder Maxwell Hazen said he could see that Danny had the ambition to create a unique and successful business, if he was given a break with time and resources. “He was different in the best way possible,” Hazen recalled. “His mind worked in the same way as only a few people I know who are very talented, and at the top of their game.”

For their part, his mother and stepfather Eddie were very supportive when Danny wanted to open his store. “Don’t worry about failure,” Ms. Ives told him. “It’s what makes someone not knowing the answer yet OK.” And when he did open the doors, his family and universe of friends – and even Maplewood mayor Frank McGehee were front and center. There, Ives greeted all arriving guests with hugs and thanks, but seemed most pleased when children with BMX bikes came by to look through the store, leaving their bikes on the sidewalk outside — reminding him, no doubt, of his younger self. “Hey guys,” he told them on that cool spring day, “come by anytime and see me; I’ll teach you to fix your bike, and learn about the parts.”

Danny loved kids, and by all accounts was as generous with his time with them as he was with the adults he met in life. On Nassau Street in Orange, where he lived for a time, Danny would fix the local kids’ bikes for free. “Me and another friend got all the kids to start calling him “Uncle Danny”,” smiles Zichelli.

Perhaps children loved Danny Ives because his life philosophy was a combination of childlike wonder, and wisdom. “Danny was like a big kid,” says Brianna Medina, “and some people may have thought he still acted younger than he was, but actually, Danny was very wise, an old soul, and knew exactly what he was doing.” She added, “When other people might suggest he should live a different way, he would disagree, saying, “Why wouldn’t I do things the way that I want to do them? Why hold back?” Danny was nothing if not authentic, and Medina said with sadness, that Danny also knew very clearly that the way he lived his life might mean he wouldn’t be around forever.

In person and in photographs, Ives’ personal philosophy was always on display. The desire to remember where you came from, who and what made you who you are – especially your childhood. “#flashbackfriday Back when we would wake up at 5 am to shred before the shoobies and security guards hit the streets,” he wrote on Instagram in 2017. “Back when we didn’t have responsibilities, we were just kids being kids. Back when we would steal [sic] red bulls and candy from A&P, then go hit up Pathmark for lukewarm bagged fried chicken,” referring to fond memories that went with photos of Danny doing daring BMX tricks as a teen. And, it was no different than the many ways people remember him, with tremendous admiration, and love. Perhaps, it could be summed up as the drive to live life hard, well, and with kindness, while still retaining your childlike sense of fun, and wonder. “I haven’t changed a bit,” he wrote. “I’m still that kid! It’s the secret to my slow aging process – never grow up. You’ll get old quick.”

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to the GoFundMe fundraiser for the Danny Ives Foundation, or to the newly established Daniel Ives Imaginative Mechanics Scholarship through the Columbia High School Scholarship Fund, which will annually recognize a senior or graduate in need who shares Danny’s passion and creativity for mechanics or robotics by enrolling in a vocational/technical school or related program after high school. Donations can be made at chssf.org (in special instructions, donor should put “Danny Ives”), or checks may be mailed to:

CHSSF, PO Box 315, Maplewood, NJ 07040

Relatives and friends were invited to attend the Funeral Mass at Our Lady Of Sorrows Church, 217 Prospect Avenue South Orange, NJ on Saturday, September 12th, at 10 AM. Since only 150 people will be admitted due to COVID restrictions, the service were be live-streamed and broadcast outside via this link: https://youtu.be/8peKPQEO2Yk

Interment will be private.

A public memorial for children will be held this Sunday, September 13, at 1 pm, Maplewood Skate Park at Maplecrest. Children are invited to bring bikes, skateboards, or skates, and all are welcome to celebrate Danny’s life in the place he loved.